A central promise in both the Republican and Democratic national conventions last summer was cutting taxes. The same was true in the political ads from every level of candidates that flooded my TV programs, inbox, and text messages during the Fall campaign. In fact, at least since the Reagan administration, all we have done is cut taxes.

However, it is vital to analyze the potential societal consequences of such decisions. While it may seem appealing to pay less taxes and have more money in our pockets, the reality is that cutting taxes can harm our economy and society. As a social ethicist, these are the types of issues within my expertise. This blog post will explore why cutting taxes is a very bad idea, especially for public education in the United States.

U.S. Taxes Are Not High

One of the topics related to taxes is how much we tax the very wealthy, and looking at the highest tax rate is one way to look at that issue. Federal income taxes began in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. The initial top tax rate was only 7%. However, by 1918, it rose to a whopping 77% to pay for World War I. During the roaring 20s, it dropped to 25%. However, during the Depression of the 1930s, it rose to 63%, then rose to as high as 94% during World War II. During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it never got lower than 70%. Then, the cuts began. In 1981, it decreased to 50%. In 1986 it went down to 28%. In the 1990s, it went back up to 39.6%. The top rate has fluctuated since then but has stayed in the neighborhood of 40% ever since. Of course, the rate does not reflect what is paid because of deductions and different rates for capital gains or special investments such as municipal bonds. Nevertheless, a 40% rate is quite a reduction from the high point of 94%.

Assuming that most of those reading this post are not in the top tax bracket, let us explore taxes for the rest of us. We may all feel like we pay a lot in taxes. Comparing the taxes among countries is complicated and can use various measures; however, virtually every study finds that U.S. taxes are low compared to other developed countries. The most standard way to measure it is based on how much total taxes (at all levels) are collected compared to the nation's GDP (gross domestic product). U.S. taxes are lower than those of other developed Western countries on that scale. For instance, at least 31 nations have higher taxes when taxes are compared to GDP.

Beverly Bird summarizes the key takeaways from a study conducted by The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which is made up of 38, primarily western and developed, countries:

Hopefully, the above should dispel any myth that U.S. taxes are high. If you doubt me, do your own research. I am confident that you will come to the same conclusion.

Tax Support for Education

First and foremost, it is essential to understand that taxes are the government's primary revenue source. These funds are used to finance crucial services and programs that benefit the public, such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure. When taxes are cut, the government has less money for these essential services. This can result in inadequate provision of these services, leading to a decline in their quality and accessibility.

We could explore tax support for many areas, as the U.S. under-funds everything from health care to transportation. However, I will focus on education funding since that is the industry in which I have spent my life.

U.S. government spending on education is low as a percentage of GDP. We rank 36th with 6.1%. So, the total U.S. spending on education is low based on the size of our economy. We do better on the metric of per-pupil expenditures when we combine elementary and secondary schools. In 2019, the United States spent $15,500 per student when the average for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries was $11,300. This ranks the U.S. fifth yet far behind top-ranked Luxenberg, which spends $25,600 per student. Moreover, there is a significant disparity from state to state, and our higher spending states skew our average. For example, in 2022, New York spent the most, with $27,504, while Idaho spent the least, with $9,670.

The Century Foundation found that in 2020, the U.S. was under-funding primary and secondary education by at least $150 billion a year. Moreover, we especially under-fund urban schools to a much greater degree than suburban ones, "robbing more than 30 million school children of the resources they need to succeed in the classroom."

Moreover, in what other industries do practitioners have to use their own money to buy supplies like teachers do for their classrooms? Can you imagine doctors having to use their own money to pay for syringes in their offices? Or ask their patients to donate boxes of tissues for the clinics like parents do for children’s classrooms?

Two factors have been shown to increase student achievement: class size and teacher quality. Both cost money. Educating and keeping quality teachers requires investment in those teachers, which includes salaries and continual education and training. Smaller class size most often increases student achievement. It makes intuitive sense that a student will learn more in a class of 16 versus 40. And by the way, class sizes of 40 are not all that unusual in urban schools, which are significantly under-funded. But smaller classes come with a cost. I have seen estimates that reducing class sizes nationally costs about $16 billion per student. The ethical question for us as a society is whether we want lower taxes or investment in our children, who are our future?

When we turn to higher education, most people might be surprised that state funding has decreased. In 2017, when adjusted for inflation, it was $9 billion less than in 2008. This has caused state colleges and universities to reduce faculty, cut course offerings, and close campuses. In addition, it has caused such institutions to find other sources of operating revenue. This has come from primarily two sources. The first is significantly raising tuition rates that many middle- and lower-income families cannot afford. This has also contributed to the student loan debt crisis.

The second significant way the revenue loss has been offset is through fundraising. Let me take an example from Wisconsin, where I live. However, you would find something similar virtually everywhere. In 1974, 43% of UW–Madison's revenue came from the state taxes. However, by 2023, this had declined to 14%.

At first blush, getting donations and decreasing the required tax dollars may seem reasonable. Of course, universities should seek donations. However, the problem is that those who contribute large amount want something in return. Traditionally, that has been as innocuous such as naming a building or school after them. However, as schools have become more dependent on such donations, the return donors want is much more intrusive. It influences the nature of academic freedom and bias-free research. Donors now want curriculum taught in a certain way or for universities to hire people with particular ideological bents consistent with the donor's ideas.

Again, I could give numerous examples, but let me use the University of Arkansas, which has a donor-funded program called the "School Choice Demonstration Project." The project's very name suggests the conclusion the program hopes to reach. I do not wish to impugn the professors and researchers there or the research they have done. Still, it is unsurprising that their research has found positive results from charter and voucher schools, while researchers at other places have yet to find the same degree of positive results from such schools. Moreover, such schools take much-needed funding away from regular public schools. The ethical question is, where do we want our tax dollars to go?

Other Harms From Cutting Taxes

Cutting taxes results in many other harms. The most dramatic thing is that the U.S. no longer does big things because we do not have the tax dollars to do them. In the past, we built the interstate highway system and went to the moon. We should rebuild our infrastructure, create a high-speed rail system, have excellent city transportation systems, go to Mars, and cure cancer. We are working on some of these things, but not in a big way because the tax dollars are not there.

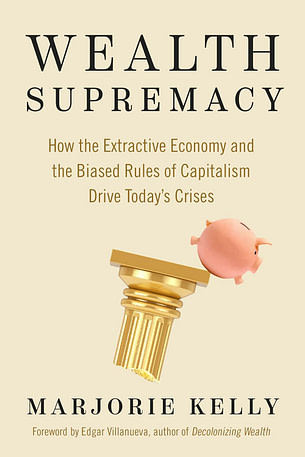

Additionally, even when targeted toward others, tax cuts often benefit the wealthy more than the middle and lower-income groups. This was especially the case for the tax cuts during the first Trump Administration. And currently, Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” will be the largest transfer of wealth from the poor and the middle class to the wealthy.

One reason for the higher benefit to the wealthy is that they tend to have a higher disposable income, which means they have more money to save or invest. On the other hand, the middle and lower-income groups tend to spend a higher proportion of their income on essential goods and services. Therefore, tax cuts can further widen the wealth gap and perpetuate income inequality.

Moreover, cutting taxes can also significantly impact the national debt. National debt refers to the money the government owes to its creditors, including individuals and other countries. With less tax revenue, the government is forced to borrow more money to cover its expenses. This, in turn, increases the national debt, which can have severe consequences for the economy in the long run. A high national debt can lead to higher interest rates, inflation, and a decrease in the currency's value, all of which can harm the overall economic stability of our country.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while having more money in our pockets may be appealing, the consequences of cutting taxes can be far-reaching and detrimental. It can lead to a decline in the quality of essential services such as education, increase the national debt, widen the wealth gap, and negatively impact social programs. As responsible citizens, we must understand the importance of taxes and their vital role in sustaining our society and economy. Instead of advocating for tax cuts, we should focus on finding ways to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government spending.

Sources

Bird, Beverly "How Do US Taxes Compare to Other Countries?" https://www.thebalancemoney.com/how-us-taxes-compare-with-other-countries-4165500 The Balance. https://www.thebalancemoney.com/ (January 5, 2023).

"History of Federal Income Tax Rates: 1913 – 2024" https://bradfordtaxinstitute.com/Free_Resources/Federal-Income-Tax-Rates.aspx Bradford Tax Institute (2024). https://bradfordtaxinstitute.com/Welcome.aspx

"How do US taxes compare internationally?" https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-do-us-taxes-compare-internationally Tax Policy Center. (2024) https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/

"How much money do states spend on education?" https://usafacts.org/articles/how-much-money-do-states-spend-on-education/ USAFacts. (2024) https://usafacts.org/

List of countries by spending on education as a percentage of GDP. (2024, July 2). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_spending_on_education_as_percentage_of_GDP.

"A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding: State Cuts Have Driven Up Tuition and Reduced Quality." https://www.cbpp.org/research/a-lost-decade-in-higher-education-funding August 23, 2017. By Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman, and Kathleen Masterson. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities https://www.cbpp.org/

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Education Expenditures by Country. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved [September 6, 2024], from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cmd.

"TCF Study Finds U.S. Schools Underfunded by Nearly $150 Billion Annually" https://tcf.org/content/about-tcf/tcf-study-finds-u-s-schools-underfunded-nearly-150-billion-annually/ The Century Foundation https://tcf.org/ (July 22, 2020).

"UW–Madison and the State Budget: Budget in Brief 2023–2024" https://budget.wisc.edu/budget-in-brief-23-24/ © 2024 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System.