Critical race theory (CRT) has sparked impassioned discussion across educational, political, and media arenas in recent years. The critical race theory attacks have, in turn, more recently mutated into attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, or attacks on anything that isn’t white and male. Our politicians have come out against just about everything that recognizes that American history and present have failed and continue to fail to build a more perfect union. It’s worth revisiting the initial focus on critical race theory because it exposes the fallacies of all the attacks.

With accusations and misconceptions swirling about what CRT really is, the public is left befuddled. To participate in these conversations, it is therefore essential to understand not only what critical race theory is, where it originated, and its objectives, but also what it is not, how and where it is taught, and why many academics and educators consider its insights valuable.

What Does Critical Race Theory Mean?

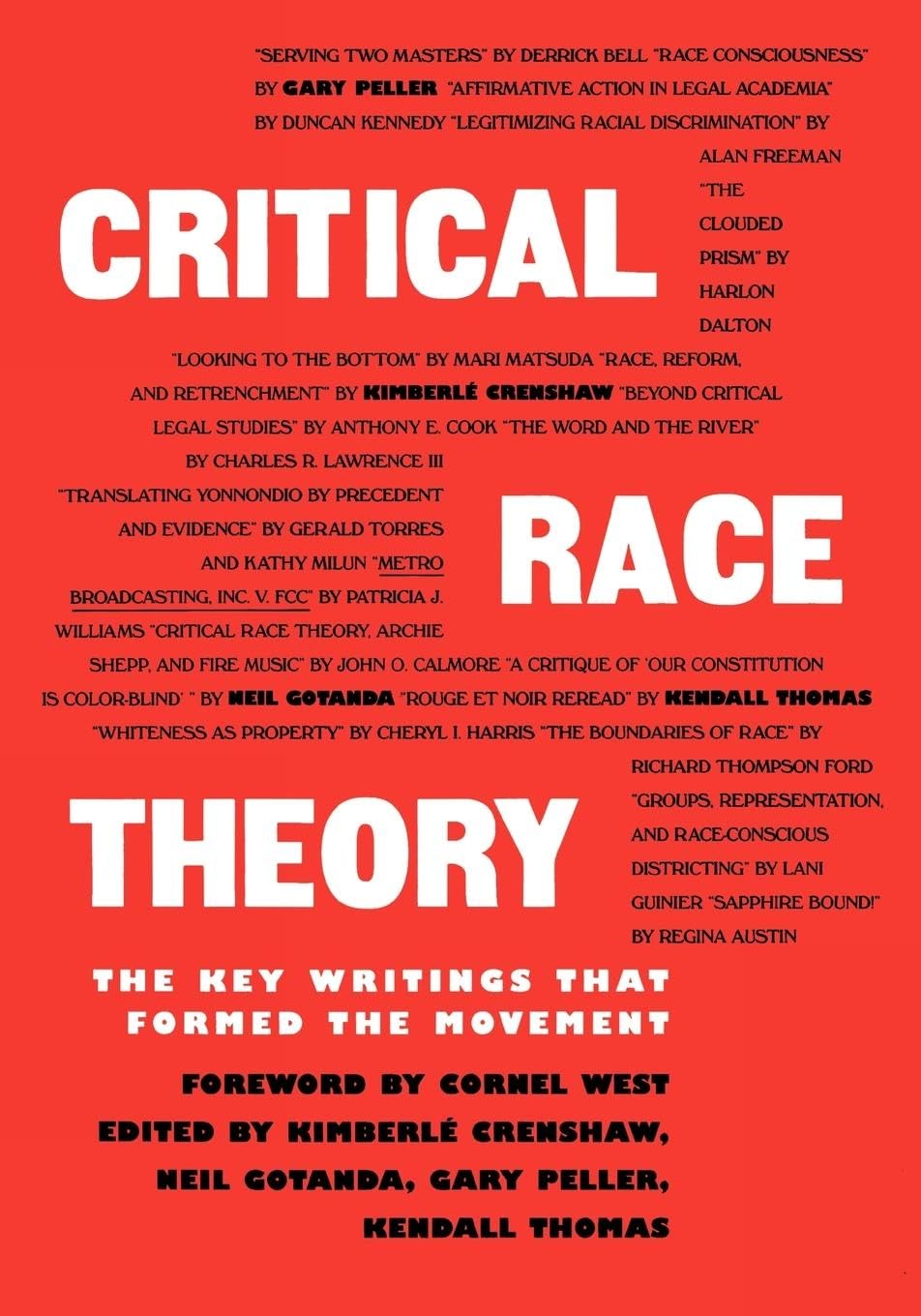

Critical race theory is an academic framework that explores the intersection of race and racism with law, policy, and society. It gained prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s, mainly through the work of legal scholars such as Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, and Patricia Williams. CRT draws on the insights of prior civil rights scholarship, critical legal studies, and activism, but diverges from them by asserting that racism is not merely the result of individual bias or prejudice but is deeply ingrained in legal systems, institutional practices, and societal norms.

CRT scholars examine how laws and policies perpetuate cross-racial disparities, even when those laws appear neutral on their face. For instance, CRT has been applied to exploring how housing, education, and criminal justice policies have produced and preserved inequities between racial groups in the US. CRT is not a single doctrine, but a family of interrelated concepts and practices, such as the following central ideas.

• Racism is ordinary, not aberrational: CRT begins from the assumption that racism is everyday, a daily experience for most people of color, not an isolated occurrence.

• Interest convergence: Progress for racial justice usually happens when it serves the interests of the dominant group.

• Race is a social construction: CRT maintains that race is not a biological truth, but a social artifact that changes over time and context.

• Storytelling and counter-storytelling: The personal experiences of people of color are essential to understanding how racism functions.

• Critique of liberalism: CRT critiques ideas like colorblindness, meritocracy, and incremental change, contending that such notions frequently mask or perpetuate systemic inequalities.

What Critical Race Theory ISN’T

Since CRT has become prominent in the culture wars in a politicized and frequently misrepresented way, it’s essential to define what critical race theory is not.

• CRT is not diversity or anti-bias training: Though CRT has impacted these larger conversations around diversity, equity, and inclusion, it is a specialized academic lens, not a course for instructing racial awareness in offices or classrooms.

• CRT is not a K-12 curriculum: CRT is not taught in American elementary, middle, or high schools. It’s a sophisticated academic tool of analysis most found in graduate classes, especially in law schools and social science departments.

• CRT doesn’t teach that all white people are racist: CRT looks at systems and structures, not individual innate qualities. It examines how institutions can inadvertently perpetuate racial injustice.

• CRT is not about guilt or shame: CRT seeks to identify and comprehend these patterns of inequality, not to cast blame or engender resentment.

• CRT is not a Marxist or anti-American conspiracy: CRT is its own legal and social scholarly tradition, not a subversive ideology designed to unravel democracy or to stoke anti-American sentiment.

In Which Grade is CRT Taught?

One of the most enduring CRT myths is that it is taught in K-12 schools. Critical race theory is a sophisticated, higher-level theoretical perspective and is virtually only encountered at the post-secondary level, especially in:

• Law Schools: CRT was born in the law and continues to be a staple of numerous law school courses covering civil rights, race, and the law, or constitutional law.

• Graduate Programs: CRT can be found in some graduate courses in sociology, education, ethnic studies, public policy, and social work.

• Sometimes at the Undergraduate Level: A few upper-level undergraduate courses may reference CRT or weave it into their coverage of race, racism, and inequality.

Though K-12 curricula can cover the history of racism, civil rights, and social justice, these are not equivalent to teaching CRT as a theory or analytical tool. The confusion tends to occur when more aspirational notions of equity, inclusion, or multicultural education are misrepresented as CRT.

Why CRT Is Useful

To truly grasp the value of CRT, it’s essential to examine its real-world impact and its potential to contribute to a more informed and just society.

1. Providing a More Profound Insight into Inequality

By examining the systemic and institutional causes of racial differences, CRT helps describe why certain inequities persist even in the face of legal equality. It promotes the review of policies and practices that implicitly marginalize certain groups, leading to more effective reforms.

2. Encouraging Critical Thinking

CRT encourages intellectuals and students to interrogate presumptions, disrupt prevailing narratives, and explore new viewpoints. It develops analytical skills and fosters a more nuanced understanding of history, society, and law.

3. Increasing Marginalized Voices

One of CRT’s gifts is its insistence on narrative and the personal experience of the oppressed. This attention complements intellectual conversations and may inspire broader policy decisions.

4. Fostering Productive Discussion

Instead of trying to close down debate, CRT wants to open it up. It aims to spark new conversations about race, justice, and social transformation. By acknowledging that inequality is complex, CRT creates space for open discussion and collaborative reflection.

5. Guiding Social and Legal Change

CRT’s insights have shaped landmark court cases, diversity efforts, and policy changes. Its impact is still felt in discussions around affirmative action, policing, education reform, and housing policy—all topics where a knowledge of structural forms of inequality is key.

Warnings and Caveats

CRT is a helpful tool, but it has its detractors. Critics contend that its emphasis on systemic racism can overshadow personal responsibility or be divisive. Others fear that it can breed hopelessness about the potential for change. CRT is contestable and changeable. Engaging with these critiques is part of the healthy evolution of academic thought.

Conclusion

Critical race theory is a high-level academic theory about the effects of race and racism on laws, society, and institutions. It’s not a children’s curriculum, and it’s not a shame-and-blame program. CRT provides potent instruments for analyzing entrenched disparities, encouraging incisive reflection, and cultivating a more welcoming world. Meaningful conversations must be based on a correct understanding of what CRT is—and what it isn’t. In this process, we can more effectively address the demands of our shared past and move toward greater justice for all.